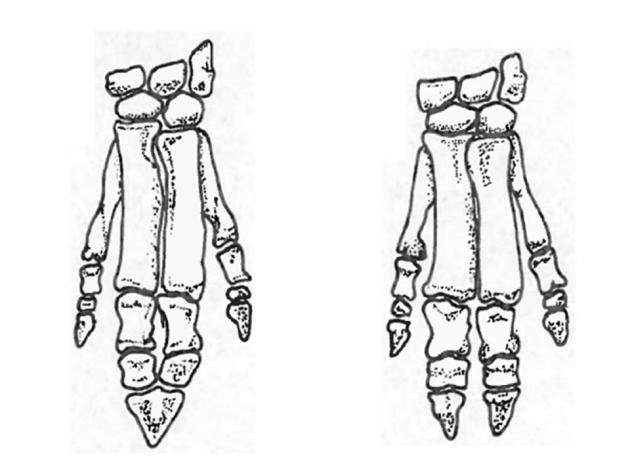

One uncommon feature that has been reported in feral hogs (also called wild hogs; Sus scrofa) is the presence of syndactylous or “mule-footed” hooves. The mule-footed condition in swine is structurally only a slight variation from the normal cloven-hoofed condition. Internally, it is caused by a developmental fusion of the last pair of bones of the two middle toes or digits of the foot (Fig. 1). In some cases, the next to the last toe bones can also be fused into a single structure. Externally, the fusion of those two digits gives the appearance of a single, central-toed hoof similar to that found in equines, hence, the name “mule foot” (Fig. 2). The lateral digits in the mule-footed condition appear to be normal. The track left by mule-footed hogs has a large central print, which is flanked by prints from the lateral toes (Fig.3). Not all mule-footed hogs have the condition on all four feet. Although having all four feet either cloven-hoofed or mule-footed is the most frequent condition that one finds, feral hogs have been reported as having anywhere from one up to all four feet with mule-footed hooves.

Figure 1. Illustration of the bones in the feet of a “mule-footed” and a normal cloven-hoofed feral hog.

Figure 2. Posterior foot of a feral hog exhibiting the “mule-footed” condition of the middle toes.

Although it has never been abundant, the mule-footed condition in swine has been recognized for a long time. Aristotle, the Greek philosopher and teacher, first recorded the existence of this trait in about 350 BC. In the late 1800s, the naturalist Charles Darwin noted that this condition was occasionally observed in swine in various parts of the world. Officially, the “mule foot” as a domestic breed of swine was started in Ohio in 1908. However, even though the breed originated in this country, it was never widely distributed. Initially reported to be immune to hog cholera (currently referred to as classical swine fever), these animals became popular shortly after the breed was initially registered. However, this reported immunity proved to be unfounded, and the breed gradually declined.

Figure 3. Track of a “mule-footed” feral hog.

As with many types of domestic swine in the United States, mule-footed hogs have over the years been released into free-ranging husbandry conditions or escaped from confinement to become wild-living. Feral hog populations exhibiting the mule-footed condition have and, in some cases, still do exist in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Texas, and California. Other states that have reportedly produced mule-footed feral hogs include Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. However, the documentation of these occurrences is sketchy, and thus the authenticity of such animals remains questionable. In general, however, feral hogs exhibiting the mule-footed condition are seemingly becoming rarer. According to experts at the American Minor Breeds Conservancy, domestic populations of this breed are now almost nonexistent.